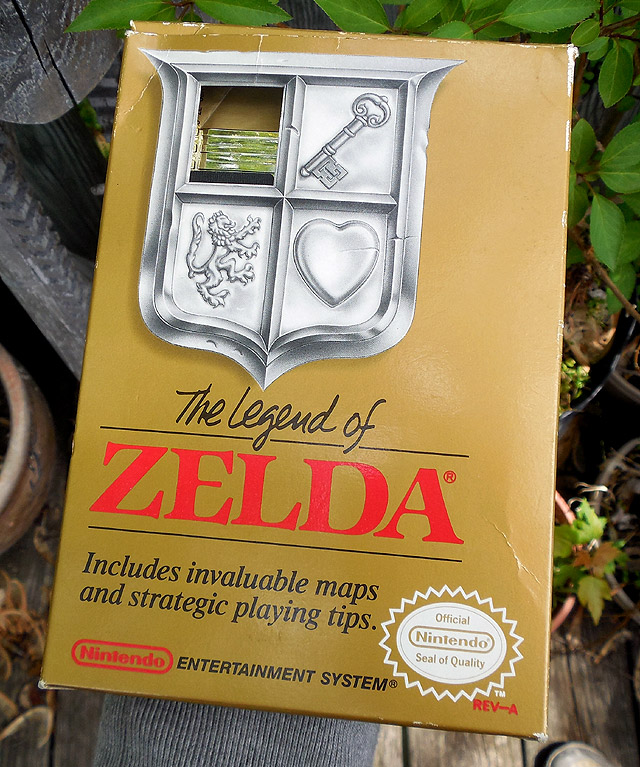

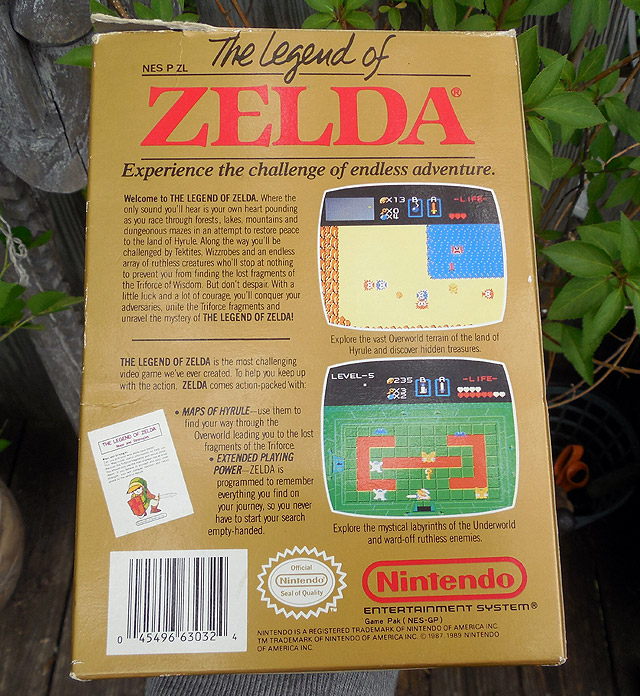

While digging through some more old storage bins, I came across that.

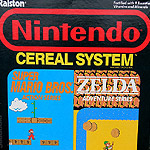

The Legend of Zelda, for the Nintendo Entertainment System.

Finding an old Zelda cartridge might normally only be cause for a passing smile, but this was different. This was 100% complete, in its original box, with the manual and everything.

I even have the foam block.

Maybe I’m wrong or maybe I’m just old, but I feel like today’s kids couldn’t possibly understand what it was like to get a NES game. It was a different sort of experience. Keep in mind, I’m not calling it a “better” one. Just different.

The game – meaning, the actual playing of the game – was only the half of it. I got just as many jollies from the tangible parts. The box, the cartridge, the manual. Sure, these things still exist, but do they have the same feel?

Today’s games – again, the tangible parts – are more like DVDs. They may be packed nicely with great cover art, but you wouldn’t exactly handle them with rubber gloves. You wouldn’t put them on pedestals, proverbial or not.

(And yeah, I’m excluding super special fancy releases that come with wild bonuses. There are exceptions. I’m speaking generally, here.)

When I got a new Nintendo game, I treated it like a freakin’ puppy. I wanted the box to stay in mint condition forever, even if it never did. I’d place it on my shelf like it was a sports trophy.

And the manuals and other paperwork? God! I didn’t look at my Nintendo manuals like simple tools to help me play more effectively. To me, they were real books. From the story summaries to the intense illustrations, I spent more time reading and rereading certain manuals than I spent playing their associated games.

So yeah, this could be another case of someone believing he had a wholly-different and possibly-better version of what “them kids today” have, but if I had to pick one game to support an argument that it isn’t, I’d go with The Legend of Zelda.

I still remember the moment I got it. (Not this exact copy. This was a secondary market pickup. I mean my really real-deal original.)

Christmas Eve, 1987, at midnight. Which I guess was technically Christmas morning.

I was eight-years-old.

Zelda was that year’s biggest “brag gift,” and I couldn’t wait to tell my friends about it. Hey, by that point, Nintendo already had time to make Zelda seem like the biggest thing ever. The TV commercials ranged from vague to epic, but they all pleaded the same case: This was NOT a normal video game.

You might imagine that I dived right into Zelda, but actually, I didn’t. I put the box in a safe place and busied myself on my bedroom floor, far more interested in my other Christmas gifts. (This will not surprise anyone who reads me. Video games always came second to toys.)

I’ll never forget that feeling. Minutes into Christmas, and I’m in hog heaven on the floor, fiddling with my new Serpentor. (The one with the sparkly green cape — swoon!) If I remember things correctly, Serpentor battled against some Real Ghostbusters figures. Every now and again, I’d look up from the floor and spot that sealed copy of Zelda on the bed. Wow. Even after my new toys got boring, I still had THAT to deal with.

It was the kind of material ecstasy that only a child could fully embrace, and brother, did I ever embrace it.

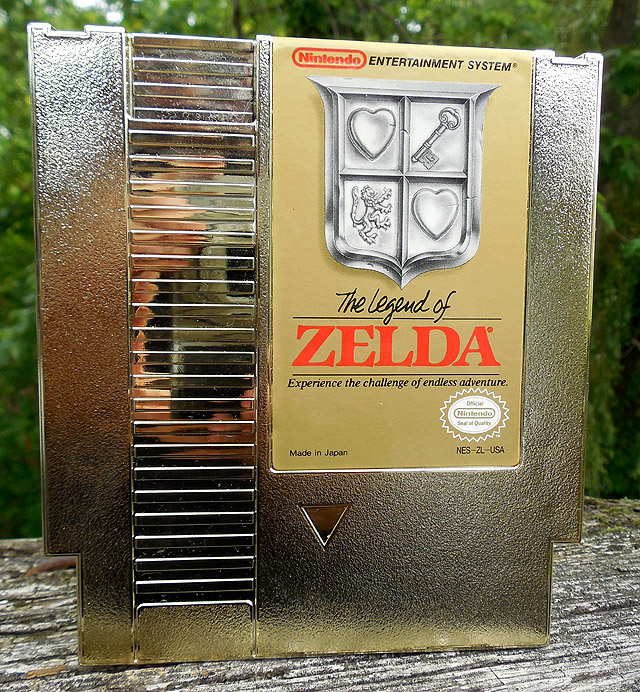

The fact that the cartridge was gold was an enormous deal. I don’t know enough about gaming history to rattle off titles that did anything this awesomely gimmicky before Zelda, but this was certainly my first experience with it.

When we were kids, fake gold was real gold. I’m not saying that we were too stupid to understand the differences between a Nintendo cartridge and our parents’ wedding rings, but when we got something this shiny and this gold, it HAD to be special.

Not just “different.” Special. Special and valuable.

The gold thing immediately set Zelda apart from every other Nintendo game I had. How could it not? All of my other cartridges were slate grey. I was never too good about keeping my carts in their sleeves, but I was much better about that with Zelda. I felt like I had to be. It was GOLD, after all.

You were supposed to protect gold.

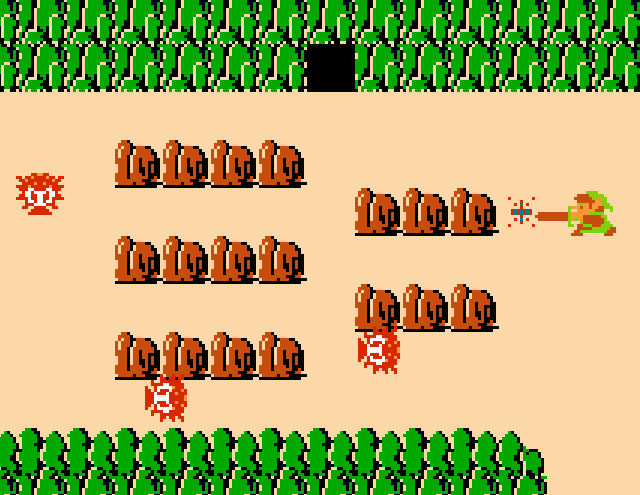

The Legend of Zelda became one of my favorite games, but it didn’t hook me immediately. Honestly, for the first few days, I found it kind of boring.

That was my own fault. I was impatient and new to this sort of thing. Until then, I liked my games “instantly awesome” or “instantly easy.” If it was too hard, or if I didn’t immediately understand where everything was headed, I tended to balk. At first, I only gave Zelda five or six minutes a pop to work its magic. That wasn’t fair.

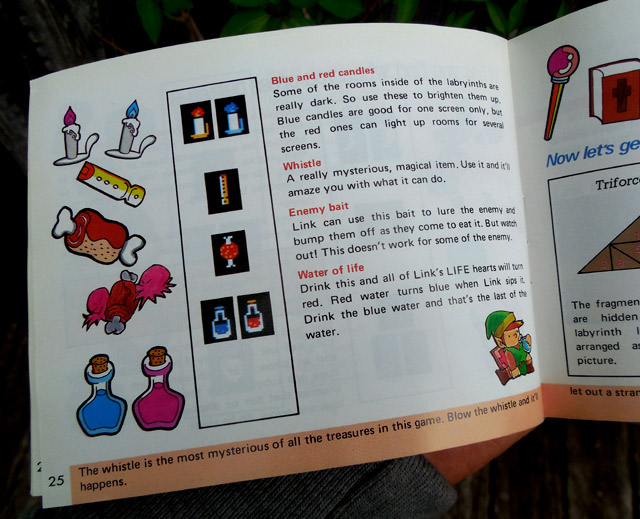

What got me to start seriously investing in Zelda was its manual, and not just because it made the gameplay clearer. I hate to be so firm in an area that’s this subjective, but Zelda had THE BEST MANUAL EVER.

DON’T YOU DENY IT.

Here’s where I get nervous. The next few paragraphs need to click.

Compared to other Nintendo games, Zelda’s manual was HUGE. Part of that was a byproduct of needing to explain so much more than most games required, but that isn’t the part I want to focus on.

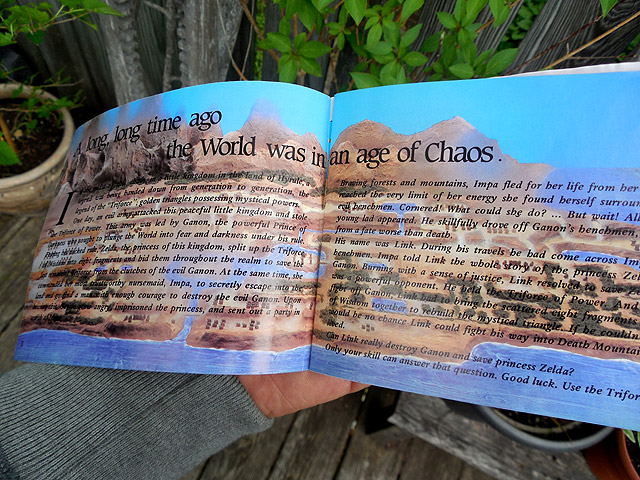

Moving past the “here’s how you do this” and “here’s where to go next” portions, the best pages of Zelda’s manual simply defined the story. This wasn’t your usual paragraph or two!

“A long time ago the World was in an age of Chaos.”

Even from the opening words, the shit had hit the fan. The first two pages read more like a summary of The Lord of the Rings than a video game back-story, and it only got better from there.

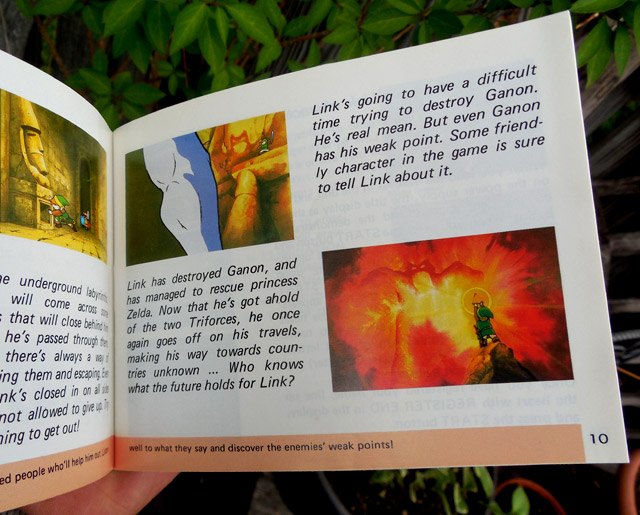

Next was a six-page feature, titled “Hints on How to Destroy Ganon.” But it wasn’t really about that. There were tips on how to get from Point A to Point Z, yes, but the way they packaged those tips was phenomenal. The entire story of the game was told in a present tense narrative, accompanied by incredible illustrations. (“Illustrations” is saying too little, because they looked more like cartoon cels. To the point where I’m still not sure that they weren’t.)

This section ends wonderfully, with hints – but only hints – of what Ganon actually looked like. For a short while, that was the great unknown. Sure, even official Nintendo publications eventually spoiled it, but the manual sure didn’t.

(At the start of my journey, I’m not sure what motivated me more: Saving Hyrule, or seeing Ganon.)

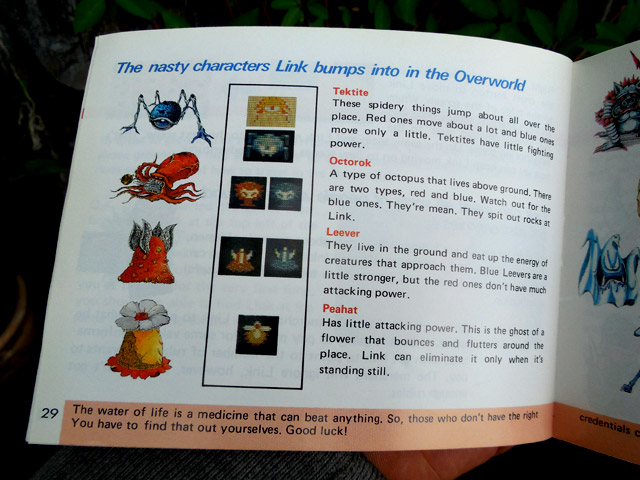

The manual continued being great with a breakdown of Link’s many enemies. MY GOD. While playing Zelda, the diversity of Link’s enemies was something to behold, but the pictures in the manual made you appreciate them on a whole different level.

Take the Tektites. In the game, they were presented as one-eyed bouncy spiders. That was cool, but compare it to the manual’s illustration of a bumpy, four-legged monster that looks like it crawled out from The Mist.

The manual’s drawings drove me to the biggest heights of elementary school fame. So enamored was I with those monsters that I began a class-wide “Zelda club.” The whole point of that club was to draw Zelda enemies on looseleaf paper. We all kept our doodle collections in super professional manila folders. It was great.

I must’ve drawn a hundred Digdoggers. In retrospect, that was probably because he’s so easy to draw.

“Circle. Okay now another circle. And we’re out.”

It was the same thing on the pages that listed Link’s items. The illustrations even made “enemy bait” look like some weird ass but totally desirable toy.

And all of the above only scratches the surface! Zelda’s manual was 46 pages long, so when I say that I treated it like a “book,” I’m only stretching things a little.

And I’m not stretching things at all to say that this “book” meant as much to me as the game.

Maybe even more.

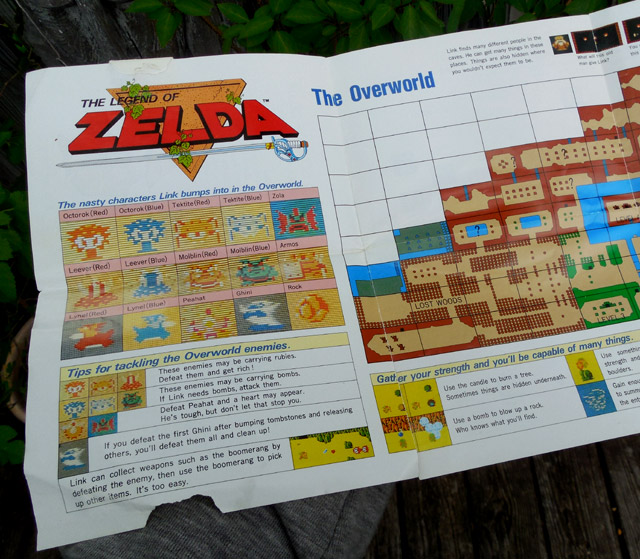

Solidifying Zelda’s position as the game to have the most incredible ephemera in Nintendo history, you also got a big foldout map. This was critical, because most of us weren’t used to worlds this huge and complicated.

(Actually, Zelda may have marked the first time when I really had to know more than what the game told me. In 1987, you didn’t expect to create new pathways by setting fire to bushes. That was a far cry from making Thomas beat up ninjas in six straight lines.)

You’ll note that I spent very little of this post talking about the game itself. That was the point! Zelda was going to be special even without the hubbub or gold cartridge, but considering all of that and everything else, the whole experience of getting it and owning it and living it became so much more.

And Zelda was a unique example, okay, but I treated all of my Nintendo games with a similar reverence. The parts that existed in the the real world mattered as much as the parts on the screen.

Does that still happen today? I’m not being rhetorical, here. I’m honestly curious. I don’t play much of anything these days, but having seen my nieces and nephews receive more games than I could count, it always seems like they’re “in one eye and out the other.” Like the kids save their excitement for when they actually play.

It was different with Nintendo games, and I guess just “older games in general.” It was like going out to dinner and getting to keep the plate. Maybe you’re eating better today, but you ain’t getting no plates.

Am I overstating things? Maybe I’m just too disconnected from what’s out there to make a fair comparison. Maybe I just desperately want to believe that I had something that can’t be duplicated. I admit that there’s a 75% probability of this.

In which case, at least I took a pretty sweet photo of Zelda’s box.

Well lit and nicely composed!